To

understand the origins of youth and youth culture in the 1920s, we have to look

at the extension of schooling: the development of high schools and universities

as public institutions which not only serve the elite and privileged but also the

masses of youth in the middle class and the working class. We see the

importance of extended schooling in terms of its effect of bringing young

people who are all the same age together in the same space, in the development

of “peer culture.” The young people don’t have to work or build a career yet,

and they are young so they want to have fun, be entertained, also find their

identity, express themselves at the same time that they want to be part of the

group and “fit in.” And some of them—not all but a lot of them—are also young

and want to experiment with their sexuality, and find some means of getting intoxicated

through alcohol/drugs.

Two

peer cultures which developed and expanded during the 1920s. The first is the

greek system of fraternities and sororities which expanded as the universities

and high schools expanded in the 1920s, along with college football and sports

and a series of fads and fashions which involved how one could dress

“collegiate,” master the “collegiate look.” The second peer culture involves

the culture which developed outside of school, at night on weekends and in

movie houses and jazz clubs and places of amusement. It is here that we see

changes in attitudes about sexuality and gender roles, the emergence of the

“dating” system and increasing rates of premarital intercourse, a series of

changes which had their most profound effects on young women. One indication of

those changes is the emergence of a subculture of “flappers,” which we see as a sign, symbol of the

changes taking place with respect to young women, sexuality, and gender. The

flappers were based in the jazz clubs during Prohibition, and they also represent

important developments in race and its relationship to music made by

African-Americans.

These

youth cultures which developed during the 1920s were eventually stifled by the

events that followed, the Great Depression and WWII. Young people no longer

able to insulate themselves from work and responsibility, they had to “grow up

fast” while looking for a job or fighting a war. Not until the 1950s would

young people and youth culture be as visible in American culture, and by that

time it would be continuous but also bigger than ever.

Many

high schools and universities were founded during the 18th and 19th

centuries across U.S, but they mostly serviced the elite. Private colleges in

particular were places where rich went to become “refined,” how to do things

like learn Latin, which has no practical application in the real world but is a

way of showing privilege. They went to college for religious study. Colleges

were private, expensive, but most of all you had to have the privilege of not

needing to work to help your family. In the year 1900, only 1 of 9 of 14-17

year-olds were in high school, and much fewer in college. The vast majority of

teenagers worked on farms to support their family or maybe even feed their own

family, or they worked in a factory or somewhere else because the family needed

their earnings.

Enrollments

in high school and college began to rise steadily in late 19th and

early 20th century, but 1920 was biggest period of growth. In 1920,

there were 2.2 million HS students, but by 1930 that number had nearly doubled

to 4.3 million HS students. In 1920, 28% of American youth had attended at

least some high school; by 1930 it was 47%. Colleges also saw their enrollments

triple within a 30 year span, from 1900 to 1930. By 1930, 20% of people in late

teens and early twenties were in college. College was still relatively

exclusive to the middle class and some segments of white working class, while far

fewer numbers of blacks and racial minorities were attending. Actually more

women (slightly) than men enrolled, because men’s labor was more likely to be

valuable.

|

Why

this growth in college enrollment? The 1920s saw a tremendous expansion of

middle class, which had been growing for some time but accelerated its growth in

the 1920s. The new middle classes were based on “white-collar” jobs, jobs not

in manual labor but insurance, sales, management, engineering, or the

professions. This sector of the American population experienced much prosperity

throughout the 1920s, as wages and incomes increased steadily, the stock market

prospered, and the consumer economy flourished as people had more money to

spend. The new middle class was based on white collar jobs in corporations,

based not on physical skill, but rather on information, knowledge,

organization, leadership, services, decision-making, or in other words mental

and social skills. Corporations wanted people with more training in

intellectual skills, with more years of schooling. In turn, people in the

middle classes and the working classes who wanted their children to have a

better future for themselves saw that schooling was the path to upward

mobility, the best and maybe the only way of moving into a white collar or

professional career. So if families could at all afford to send their child to

high school and college, if they didn’t

need their child to work to help support the family, they would send them to

school in hopes that it would give them more opportunities for the future.

One

crucial consequence of the extension of schooling is not only that it allowed

more people to reach or at least aspire to middle class life, but also that it

brought people the same age together in one space. It created the conditions

for a “peer culture” by concentrating them in school. At school, young people

were away from their family (maybe even living at school), they were surrounded

by people their own age, and they were relatively autonomous from institutional

authority. All schools certainly had and still have an elaborate number of

rules and regulations and disciplinary measures and rules of conduct and dress

and authorities (teachers, deans, etc.) who are in charge of watching over

young people. But they are less stringent than in something like the military,

where young people are concentrated together but have absolutely no freedom to

act on their own, and this is why sociologists call the military a “total

institution,” as opposed to high schools and colleges.

|

The

first “peer culture” in relation to school. These were mostly school clubs based

on extra-curricular activities. High schools and colleges saw students become

involved in after-school dances, drama clubs, glee clubs and choruses, as well

as participation in student government and student newspapers, and all kinds of

different religious and ethnic organizations. These student groups tended to

act as a bridge between family and adulthood for young people, providing them

with emotional support and friendship and security among their peers and thus

easing the removal from one’s family, while at the same time giving young

people opportunities to make their decisions, work together as a group, and

participate in ways that they couldn’t do in the classroom.

The

most important and central of these school-based peer cultures was the greek

system of fraternities and sororities, which were closely connected to school

athletics and team sports, the most popular of which was football. Again,

fraternities and sororities had been around long before the 1920s, on both HS

and college campuses, but the 1920s was when they experienced an extraordinary

growth as enrollments increased. The number of fraternity chapters increased

from 1,500 in 1912 to 4,000 in 1930. The number of fraternity houses increased

from 750 in 1920 to 2,000 in 1930. By 1930, 35% of college students were in

fraternities and sororities.

|

Greeks

were thus a minority, but on many campuses they became a very powerful and

influential one. At most schools they dominated student government and, by

extension, student newspapers. In fact, most elections were simply choices

between different fraternities and sororities. As they received more alumni

donations and build more houses around campus, they also began to wield

considerable financial and political power. By 1929 the estimated value of all

greek-owned property was said to be $90 million.

But

the place where Greeks probably exercised the most power and influence was over

the social scene, the peer culture of young people on campus. Fraternities and

sororities built their reputation based on having the most popular, the most

important, the most attractive, people. As enrollments and pledges increased,

the Greeks could afford to be more and more selective, and their reputation in

fact hinged on being the most exclusive, the most selective. Because of their

power in student government and newspapers, they could increase their own

status and prestige by electing their people to positions of power or writing

articles in the school paper about the “big man on campus.”

The

most important way that frats and sororities enhanced their prestige and status on

campus was through linking themselves to college football. The 1920s saw an

explosion in interest and popularity in football at the college and high school

levels. Football was popular because it resolved people’s anxieties about

masculinity in the 1920s: young men were no longer fighting at war, nor were

they working in factories or farms, but instead they were in school, an

activity that at the time had feminizing connotations. So people were basically

afraid that little Johnny would go off to school and come back a pansy, and

football helped eased those anxieties because it was so masculine and violent,

a sport that most closely approximated warfare. Football also helped galvanize

people’s sense of “school of spirit,” their sense of belonging to something larger

than themselves, being part of the glory of their institution. When the team

won, they won. During the 1920s students would often travel with the football

team for games at other campuses, taking a “road trip” from Ann

Arbor to Evanston to see Michigan

Fraternities

and sororities latched on to the power and popularity of college football

during the 1920s. They aggressively recruited the best and most attractive

players and cheerleaders among themselves. When people on campus thought of a

particular fraternity or sorority, they often associated it with an individual

player or cheerleader.

Because

they were seen as powerful, because they had a reputation, status, and prestige,

most students invariably wanted to be part of the Greek system. Most students

had been sent to college in order to become “successful,” and fraternities and

sororities were the most immediate symbols of success. Sometimes the benefits

of belonging were economic, because of the connections that alumni might have

with business or government. But the Greek system was also crucial for things

like the dating scene, where one’s attractiveness and desirabilitiy of course

resided in which fraternity or sorority one belonged to. If you needed a date

for the big dance and didn’t belong to a reputable house, you were probably out

of luck.

|

Because

enrollments were increasing rapidly and because so many of those new students

wanted to be part of the Greek system, and because the fraternities and

sororities based their reputation on being selective and exclusive, the campus

peer culture of the 1920s was extremely conformist and hierarchical. If you

wanted in, you had to talk the same, dress the same, act the same, and share

the same values, ideas, and attitudes as your peers. If you were too weird, if

you didn’t show enough “school spirit,” if you had too many intellectual

interests and not enough extra-curricular ones (not to mention if you were not

attractive, or Jewish, or black), you could be easily discarded and left out.

|

This

pressure to fit in and keep up with one’s peers became even more intense during

the 1920s with the introduction of “fads” and various “collegiate” fashions.

Now students not only had to keep up with their peers but also stay informed

about the newest fashion, the latest dance craze, and so on. College newspapers

circulated reports about what the students at Yale or Harvard were wearing.

Advertisers began to target college students because their numbers were

becoming larger and they had money to spend. Advertisers could exploit young

people’s anxieties about “fitting in” with the crowd, asking Didn’t you know

everyone who’s anyone is using X? Wearing Y? Movies and magazines, the newest

media of the 1920s, also helped circulate images of what the young and

successful were doing and wearing. In short, this peer culture on campus was

based on a precarious balance of conforming to group expectations and competing

to be the newest, the hippest, the most modern.

|

|

A

second form of youth culture became highly visible during the 1920s, and this

one developed outside of school. This doesn’t mean that high school and college

students didn‘t go out to nightclubs, to dance and listen to jazz music, to

drink and mingle with the opposite sex, etc. because they did—middle class

students were an important part of this youth culture also. But this second

youth culture also involved a lot of young people who weren’t students,

working-class youth who were the children of immigrants, who lived in cities

but didn’t go to school and had to work in their teenage years.

The

late 19th and early 20th centuries were an important

period of change for young people, even if they didn’t have the opportunity to

go to school. This was the period of industrialization, and the demand for

labor drew many families to migrate to the American cities, either from rural America or somewhere outside the US New York

|

The

system of dating, going on dates, as we know it, emerged during the 1920s among

young people. Previously, courtship had been strictly chaperoned: young people

could go out with the opposite sex, but they had to bring an adult or be

subjected to adult approval. The date was different because it was relatively

unsupervised. The availability of the automobile was crucial to this freedom,

as the date involved going out somewhere, and the automobile might also be the

place where the couple ended up if things got serious. Sometime in between, the

couple had to have somewhere to go, and dance halls and amusement halls were

certainly popular, but the most popular destination was the movie theater.

Going to the movies, after all, not only meant going out but also sitting alone

in a dark theater.

The

movie theater became an important destination for young people—during the 1920s

it was reported that most young people went to the movies about once a week. In

turn, the movie industry began to target

young people as a crucial audience and source of profit. Moviemakers tried to

capitalize on the interest of their youthful audiences with movies about people

their age: in the early 20s, there were several movies with “youth” in their

title produced every year, such as Reckless Youth, Flaming Youth, The Heart of

Youth, The Soul of Youth, The Price of Youth, The Madness of Youth, Youth Must

Have Love, Sporting Youth, Pampered Youth, Cheating Youth, and finally, Too

Much Youth. The movies themselves also became an important means of advertising

to young people, particularly to young women, as fans became interested in what

cosmetics movie stars used, what clothes they wore, what hairstyles they

sported, and so on.

More

generally, the movies provided a perfect advertisement for a life of leisure

and consumption, for a liberalization of sexual mores, for an image of the

“good life” as it appeared to be personified by youth during the “Roaring

Twenties.” This image of the Roaring Twenties was captured by the novelist F.

Scott Fitzgerald, who wrote about an age when young people ruled the scene,

when everyone wanted to get in on the good life and share in prosperity and

consumerism, when people wanted to know what young people were up to so that

they too could be hip to the newest, most modern styles, when youth themselves

were confident, carefree, and turned their backs on adult authorities and

traditions. So the image of youthfulness, especially in the movies, was closely

connected to the prosperity and consumerism of the Roaring Twenties, and to the

way in which the new consumer culture accelerated the rate of change in society

and broke down the repressiveness of the Victorian Era.

Indeed,

during the 1920s, attitudes about sex, family, work, and gender were all

changing, and young women of all class backgrounds were leading the change.

Surveys reveal that young women were losing their virginity at an earlier age,

that more young women were having sex before marriage, and that most of them

did not think of sex as a “sin.” Various magazines began to report about the

practice of “petting” among young people on dates. People became more receptive

to the idea of sex education and information about contraception, and people of

all ages were less likely to view divorce as a source of shame and stigma. The

media tended to inflate and exaggerate the changes in sexual mores and behavior

to create a sense of moral hysteria, but the fact is that attitudes had really

changed.

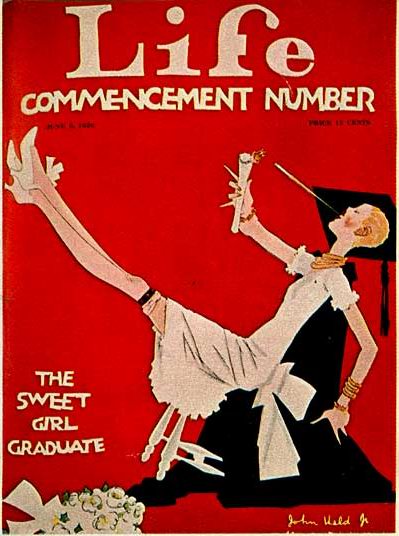

The

flapper became the symbol of these new freedoms granted to young women and the

liberalization of attitudes about sex. The word flapper was brought home by

American soldiers after World War I who used it to describe European women who

were supposedly looser and more “easy.” The flappers were both a real

subculture of young women and a figment of media sensationalism about sex,

girls, and morality. In other words, they are the first of many American

subcultures—like juvenile delinquents, beats, hippies, and punks—which have

some basis in reality, and then are hyped up in the media, which causes more

young people to want to be a part of them because the media gives the

subculture a reputation for being bad, rebellious, etc.

The

flapper look and style was characterized by bobbed hair, short skirts, silk

stockings, and heavy cosmetics. It was a conscious turn away from the image of

femininity in the Victorian era, when girls were made to look like flowers,

with frilly dresses and long hair. The flapper look was more aggressively

sexual, but the short hair and slimming fashions also gave it an androgynous

appearance. The flapper style became synonymous with the modern look, with the

style which moved away from traditional styles of fragile femininity. The

behavior of flappers also suggested a breaking with tradition in regard to

gender norms: flappers got attention because they smoked and drank in public (these

were big no no’s), because they danced with men in dance halls, and because

they had a reputation for going all the way before marriage.

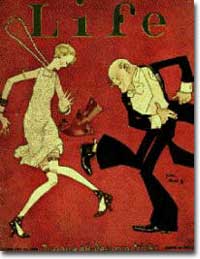

The

place where flappers could be found was in nightclubs, dancing to jazz music,

leading a series of dance crazes like the turkey trot, the bunny hug, “shaking

the shimmy.” Beginning in the year 1920, the

|

|

Dancing to jazz music and

going to speakeasies became immensely popular not only with flappers but with

all kinds of young people who were looking for a good time and a chance to

rebel. This touched off a moral panic among adult authorities, who were

predictably troubled by the sexuality of youthful dancing, especially within a

racially integrated establishment. In the early twenties, the Ladies Home

Journal warned its readers that young people were

being morally corrupted as they danced along to "the abominable jazz

orchestra with its voodoo-born minors and its direct appeal to the sensory

center." Notice the blatant racism in this warning—the description

of music made by blacks as “voodoo music,” the assumption that black music is

primitive, sensual, can somehow inflitrate the body and make it “wriggle.” This

was of course the main fear of white America about jazz, dancing, and

speakeasies: that black music might corrupt young girls by appealing to their

sensuality, that on an intergrated dance floor young white girls might “wriggle

their torso” with young black boys. This is a common formula for moral panic,

which we will see repeated in the 1950s with regard to rock ‘n’ roll: it is

basically the fear that comes when young white kids listen to black music.

You

might also notice that the young people themselves also found music and dancing

to be exciting and rebellious because they mostly shared their parents’ racist

assumptions. The parents thought that the music and dancing was primitive,

sensual, and exotic and that this was a bad thing. The kids also thought the

jazz scene and its people were primitive, sensual, and exotic, but this was

exactly what they wanted. In other words, they shared their parents’

assumptions, but reached different conclusions. They wanted to rebel or escape

from civilized, so they latched on to a people and a music which they assumed

to be uncivilized, primitive and exotic. This established a pattern of white

appropriation of black music which we will see repeated at several different

points during the twentieth century.

|

|

| Add caption |

No comments:

Post a Comment